Church steeples cast evening shadows across St. Louis highways as retreating commuters sail home to safe suburban harbors. These spires stand as testaments to our historic City’s remarkable growth while their church bells resonate with tales of urban decline. Many city churches have already closed while still more stand on the precipice as the St. Louis Archdiocese deliberates parish realignments and additional church closures.

Today’s stark realities converse the time of St. Louis’ rapid post Civil War growth when immigrants settled in ethnic enclaves of red brick homes and flats. Densely populated neighborhoods consisted of families, many of whom lived in two or four family flats. Germans made up the initial and largest immigrant group, but Poles, Irish, Italians, Czechs and Serbs soon followed.

For many, parishes served as life’s focal point. Ethnically diverse, but similarly motivated by faith, kinship and pride, the immigrants built parish edifices of schools, convents, rectories, and especially churches whose tall spires rose above them. Like their European progenitors, they designed solidly built shrines crafted by artisans, constructed to stand for centuries.

Their tithes supported the parish schools, their many children educated by religious orders of nuns who inculcating them with a Christian ethos. Students followed in their parents’ footsteps, perpetuating a venerable system. Even the most ardent anti-papist conceded that the Catholic Church and its educational and cultural system played a major and positive role in St. Louis’ expansion.

Post War Cultural and Economic Changes.

Ironically, post World War II affluence and an evolving culture changed everything. Affordable single-family homes available to a large segment of the population led to a secular exodus to the suburbs. St. Louis County government—the recipient of our myopic city forefathers who seceded from the County in 1876—pocketed a rising tax base leaving the City to bear the disproportionate burden of those with lesser means.

The federal government built interstate highways that facilitated suburban migration. Construction of Interstates 44, 55 and 70 required demolition of city housing stock replaced by wide concrete swaths that scarred and disconnected city neighborhoods while enveloping them with high-speed vehicular clamor. This demographic tidal shift resulted in ebbing numbers and finances needed to support a system designed for an earlier time.

Meanwhile, segregation settled in the city, with vacancies filled by African Americans who bore the cross of meager economic opportunity. Systemic racism left them in poverty, which in turn infected the City with collateral damage. Rents declined in relative value leaving landlords with limited means or desire to finance building maintenance. The crumbling began. Beginning in North City and spreading southward, many neighborhoods inexorably declined.

In 1950, over 850,000 people called the City of St. Louis home. Known in its’ halcyon days as America’s “Fourth City”, its population fell to 300,000 in less than two generations. During that same 50-year decline, the City’s largest denomination suffered a concomitant loss in numbers. Inner city parishes that once thrived based on densely populated neighborhoods and a high percentage of churchgoers witnessed sharp declines on both counts. By the turn of the new century, the Archdiocese’s city deanery shrank from 200,000 to 75,000. City parishes once numbered 85 fell to 48, with many of those remaining left to endure the same financial and demographic pressures.

The number of priests—once four to a parish—steadily declined adding another form of stress as shrinking city congregations vied for fewer clerics.

Indeed, religious vocations declined more rapidly than the City’s population. Once affordable Catholic schools endured the loss of ‘vow of poverty’ nuns and brothers who once back-boned a low-cost, affordable private educational system. Catholic high schools and grade schools continued to close their doors.

In another blow, the Archdiocese paid huge sums to settle sexual abuse of minors committed by a small number of aberrant priests. The resulting fall out included not only a loss of financial reserves, but of church membership as well.

Acknowledging the dilemma, Archbishop Mitchell Rozanski observed in an open letter to the Diocese: “The model that fulfilled its mission in growing and evangelizing the Church during the last century has become archaic….We anticipate that these adjustments (to our ministries and supporting structures) will be the most sweeping changes that the Archdiocese has witnessed in its history.” He added later when talking with reporters that “I don’t want to see a community that is burdened by buildings. Buildings are important, but…are not the church. It is the people who are the Church.”

How this historic restructuring plan plays out in the City remains to be seen, but the Archdiocese program called “All Things New” does not bode well for all things old. Already many of the noble sanctuaries built in Old World tradition stand abandoned in decaying neighborhoods. Others have fallen to the wrecking ball. Yet, many defy the odds and remain standing as beacons for consolidated parishes.

The story of these churches parallels both the plight and the hope of many St. Louis City neighborhoods.

St. Liborious

Perhaps no other parish so acutely symbolizes the rise and fall of an urban neighborhood than St. Liborius, the boyhood parish of former mayors John Poelker and Jim Conway.

Founded in 1855 by 40 German families, the church grew rapidly to 2500 parishioners. Their new church’s cornerstone was laid in 1888, a joyous event celebrated by 47 priests, a parade and a festival attended by 10,000 people. German born William Shickel designed the edifice known as the Cathedral of the Northside, a graceful Gothic revival church built with our renowned red brick and Grafton limestone. The adjoining rectory and convent of conforming architectural style were completed in 1890 and 1908.

The consecrated interior included a main altar with communion rail of marble with onyx inlay. An ornate crucifixion scene endowed the apse with an artistic and spiritual setting. Six auxiliary altars included shrines of the Blessed Virgin, the Infant of Prague, the Sacred Heart, St. Liborius, St. Ann and St. Joseph.

Elevated stain glass windows and frescoes depicted scenes from the lives of Christ and St. Liborius. A massive pipe organ played for over 50 years by the late Joseph Anler led a renowned choir that performed at Mass as well as outside concerts and festivals.

Known as the ‘lace tower’, the church’s intricate sandstone spire with artifacts rose 250 feet above street level. However, the sandstone began to crumble and restoration costs proved prohibitive for a parish in the throes of its decline. The tower was removed in 1965, a prelude to the parish’s ultimate demise.

In 1946, the parish faithful totaled 4,263; that number fell precipitously ten years later to 1,192, and to 501 in 1966. The Archdiocese shuttered the church’s doors in 1992, the remaining number simply too few to maintain a viable parish.

The church’s relics were auctioned amidst much controversy from preservationists. Ironically, the Archdiocese later employed the gutted building as a warehouse for religious icons and artifacts from other closed churches awaiting consignment to suburban churches far removed from their progenitors in faith.

St. Liborius Church now serves as an indoor skate park, its walls marred with graffiti. Tellingly, its old grade school now houses a juvenile detention center.

However, the surrounding St. Louis Place neighborhood, once marred by marginally habitable flats standing next to boarded condemnation sites and empty lots, has witnessed a resurgence of sorts with new homes and apartments built there in the last 20 years. Perhaps one day this once holy edifice will be utilized in a manner more befitting a reviving neighborhood.

Holy Trinity

Standing high above Interstate 70, Holy Trinity’s twin spires appear most prominently at night when the illuminated chalk-white Indiana limestone emits a heavenly aura. The French Gothic Revival church marks the third sanctuary of this historic parish established in 1848.

Designed by Swiss-born St. Louisan Joseph Conradi, a nationally renowned architect and sculptor, the church was dedicated in 1899, with 25,000 in attendance as St. Louisans exhibited a penchant for celebrating the openings of ecclesiastic edifices. The adjoining rectory was completed in 1909; a school was added in 1918.

Such auspicious beginnings could not withstand demographic decline. The Diocese quadrupled the parish boundaries by consolidating surrounding parishes: Most Holy Name, Our Lady of Perpetual Help, and the aforementioned St. Liborius. Holy Trinity once offered four Sunday masses for its large congregation; today, the church offers a single Sunday mass offered by a rotation of visiting priests. The dwindling number of Diocesan priests left this small parish without a pastor.

Parish Life Coordinator, Sister Janice Munier—whose energy belies her septuagenarian age—shepherds the small yet vibrant congregation, which consists of an equal number of black and white parishioners. Former pastor Father Reichers once described Mass at Holy Trinity as a fusion of traditional and gospel services. As oft the case in poor communities, the parishioners of celebrate mass with a joyousness that oft exceeds more affluent congregations.

Unfortunately, the Diocese, which took the over the reins of what was once a parish school that could no longer support itself, closed the century old school three years ago. Approximately 100 students lost their opportunity for an alternate educational setting, an expense the financially strained Diocese could no longer bear despite injections of financial support from the Today and Tomorrow Foundation.

Holy Trinity’s current boundaries include a collage of vibrant, albeit segmented tracts that includes Hyde Park and College Hill, historic neighborhoods sapped by blighted urban emaciation and abutting mean streets. Indeed, this struggling parish stands out in the mosaic of the North Side where good spiritual people live adjacent to bad environs and dispirited people.

Currently, the traditional Catholic objective of assisting the poor remains at Holy Trinity through the St. Vincent de Paul Society that offers social service programs, a food pantry, clothing and financial assistance and job referrals. Such efforts gives credence to the statement that by merging parishes the Church is better able to serve people rather than spending so much on building maintenance.

However, the parish’s small numbers consisting of many with their own meager incomes leaves this historic church in the sights of the Diocese’s cross hairs.

Most Sacred Heart

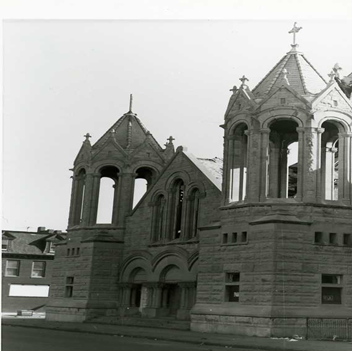

This former North Side Irish parish was founded by in 1871 by Father James McCabe who served as pastor there for 45 years. In 1898, he astutely selected Barnett, Haynes & Barnett—which later designed the New Cathedral—to create a unique place of worship for his parishioners.

Skilled craftsmen chiseled Bedford stone with pierced octagonal towers and intricate, Byzantine-style ornaments. A copper-clad interior dome enclosed an inner sanctum of unsurpassed elegance by any St. Louis church.

Sacred Heart’s 1946 yearbook recapped the year’s highlights: 114 baptisms; 93 first communions; 525 grade school students; a CYC junior soccer championship team; a total of 2,080 members. Yet, in just 20 years, the parish fell to 1300 members and 210 students.

The vital statistics continued an accelerated decline. In 1978, the church closed, announced in a tersely written decree that read in part: “… after consultation with the Council of Priests and the Archdiocesan Board of Consultors (Cannon 2292), I hereby decree the suppression of the Parish of the Sacred Hear in the City of St. Louis, Mo.”

However, the building itself could not be so easily ‘suppressed’; the campaign for its survival had just begun.

The Diocese dispensed with the church’s relics via an open auction, which served as a prelude to things to come. Many artifacts landed in private hands. Meanwhile, efforts to find a new use for the building proved unavailing. A sale for $1 to a private realty company that proposed a cultural/theatrical center for a black repertory company lacked financial viability. The handsome structure remained vacant, a frequent target for graffiti, vandalism and arson, the latter destroying the roof and marring the interior.

Despite opposition by Landmarks of St. Louis that sought to preserve the distinctive shrine, the once holy edifice was razed at the behest of Archbishop May who deemed the crumbling building “a menace to our people and a blight on our city,” an ironic eulogy for a sanctuary that anchored a community for 75 years.

The site where the church once stood—located an easy 15 minute walk from old Sportsman’s Park—along with other empty lots and boarded buildings in the surrounding area, remains vacant and useless.

St. Francis De Sales

In 1894, the parish’s third pastor, Father Peter Lotz visited Germany to study churches in his quest ‘to build the most beautiful church in St. Louis. He returned with the architectural plans for St. Paul’s Church in Berlin. His dream seems starry-eyed in context of today’s limitations where the bottom line dictates nearly every line in an architect’s blueprint.

St. Francis De Sales’ cornerstone was laid in 1895, but nine months into construction, a horrific tornado ripped through the City’s South Side, killing over 300 people, devastating whole blocks, and blowing away the church’s skeletal framework as if it were a straw hut. Delayed but undeterred, a congregation of German tradesmen completed their monument to faith and community in 1908.

The re-start cost resulted in a retreat from the original design although the end results far exceed anything built today. The church’s imposing 300-foot steeple bears four separate round-faced, Roman-numeral clocks. A 30-foot, 900 pound iron cross crowns the spire, which towered over a red bricked hamlet reminiscent of a European setting.

During the parish’s apogee, the Church centered a complex of buildings with a rectory, convent, schools for grades 1 through 12, gymnasium and even a janitor’s quarters. After World War II, the roll tallied 5,735 parishioners. But then a slow and steady decline began with the retreat to the suburbs as reflected by the membership scrolls: 1956—4,090; 1966—3,005; 1976—2,450; 1994—1200.

The high school closed in 1974. The grade school, like so many others, consolidated with three neighboring parishes, its’ numbers including a large number of Hispanic students. Ultimately, the “parish” closed, but the Church and surrounding parish campus—earmarked for demolition—was transferred to the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, a religious organization dedicated to what might be called “old church” Catholic.

Today, St. Francis de Sales Oratory serves the St. Louis Archdiocese as the center of the Pre-Vatican II Roman Rite, its credo: lex orandi, lex credenda (law of prayer, law of faith). The Oratory offers Latin masses, which includes Gregorian chants (unaccompanied sacred song dating from the 9th century), supplemented with song backed by an organ and full choir.

The Oratory recognizes the importance of Christian art in the Church’s adornments as set forth in its web page:

“Carving, gilding, painting, lace making, needlework, sewing, weaving, and many other human crafts have been developed to their present perfection because of the needs of the Liturgy, and they are, as it is, in danger of disappearing without these needs. Fine arts brought into the Liturgy are just another expression of the visible and tangible veneration that is necessary for us humans to give glory to God. As we have not only a soul but also a body, we have to show our awe towards God with both these elements that form our being. It should be clear to everyone that it is impossible to pretend to venerate God with our whole strength if we would not include in this veneration those talents and skills that He has given us to transform nature into art.”

Indeed, St. Francis De Sales’ spacious Gothic interior with ceilings that rise 70 feet high, with multiple apses, elaborately carved wood, stained glass windows, frescoes and statuary meet the artistic standards referenced above. In short, the inner sanctum pays an artistic homage to God, built with permanence that defies everything but demographic shifts.

St. Francis de Sales Church’s massive exterior and intricate interior provide the Oratory with challenging restoration goals. Since 2005, the entire roof has been restored. The stained-glass windows require restoration to limit massive heat loss; the building’s entire façade needs tuck-pointing; the frescos cleaned and restored; the 100 year-old electrical system replaced.

The massive costs of keeping this monumental church weighs heavily on the prospects for its future.

St. Cecilia

When the Archdiocese closed St. Francis de Sales as a traditional parish, the Hispanics who called it home, transferred to St. Cecilia parish.

A relative ‘newcomer’ in St. Louis, the parish was founded in 1906. An ethnic German community constructed a school that doubled as their church with the cornerstone blessed by Cardinal John J. Glennon in 1907. Thirty-one students enrolled that first semester of 1908, that number rising to 80 the following term.

To commemorate its’ 15th anniversary of its’ founding, the parishioners initiated a ‘brick shower’—donating the value of a brick multiplied by as many ‘bricks’ a family could afford—to fund construction of a church. Local craftsmen completed the handsome, ‘St. Louis red brick’ church, with twin, ‘uneven’ towers in 1927.

The church’s interior includes a shrine to St. Therese of Lisieux, ‘the Little Flower’, canonized in 1925. Stained glass windows include depictions of the Child Jesus at the Temple; Holy Family of Nazareth; Assumption of Mary; and the Crowing of Mary Queen of Peace.

The sanctuary’s byzantine frescoes stand out as St. Cecilia’s most notable artistic feature. Emil Frei recruited German artisans who hand-applied millions of pieces of glass and tile unevenly applied to better reflect light. The frescoes include depictions of St. Cecilia; Abraham; Melchizedek; the Sacred Heart of Jesus; and Mary Mother of Jesus.

A Rose Window backdrops the rear of the church, with 16 panels that includes panels for apostles and other leaders of the Church. The rear loft supports a majestic Wick Organ, with 23 ranks and 1500 pipes.

At its’ zenith, the parish grew to 1400 families, with 571 students enrolled in 1959. But like almost all other inner city parishes, it suffered a decline in numbers. However, augmented by the Hispanics who call St. Cecilia home, the school reversed the trend, with 167 students and 3,679 parishioners. Today, three of the four Sunday masses are celebrated in Spanish: Señor esté contigo.

Other Selected Historic St. Louis Churches.

St. Mary of Victories

Constructed in 1843, St. Mary of Victories stands as the second oldest church in St. Louis exceeded in seniority only by the old St. Louis Cathedral located a short walk due north.

The parish lost its housing stock long ago to the swing of the wrecking ball to make room for warehouses, the Arch and its green expanse to the north, and the Interstate and the spaghetti bowl of interchanges linking four major highways to Illinois via the Poplar Street Bridge.

Thus far, fate has saved the church from the wrecking ball.

Five thousand miles away, an exodus of Hungarian refugees made their way to St. Louis following the failed 1956 Hungarian revolution after being crushed by Russian tanks. Like all émigrés, they sought a home amongst their own, which they found at St. Stephen’s parish located at the present-day site of Nestles-Purina’s corporate offices.

The Diocese consolidated St. Stephens with St. Mary’s located a mile east, augmenting the fading German parish membership. Fifty plus yeas later, St. Mary’s of Victories still yet prevails despite the odds. But an aging congregation cannot live forever. Now deemed a Shrine, the church faces its’ biggest challenge yet when back-dropped by Archbishop Rozanski cryptic remarks about future, momentous changes.

St. Stanislaus Kostka

Perhaps appropriately, Polish immigrants settled in an area abutting a German parish, the afore-referenced St. Liborius. Construction of the Romanesque Revival Church began in 1880.

Imbued with a flinty resolve instilled by centuries of existence situated between Russia and Germany, the Polish parishioners defied Archbishop Raymond Burke when they refused to cede their parish property and church to the Archdiocese. Incurring wrath, then excommunication, the Poles held firm and ultimately prevailed in a well-chronicled legal battle against the Diocese. Today, the former parochial litigants show signs of reconciliation.

However, given the uncertainty of Archdiocese’s plans, it seems that St. Stanislaus parishioners were prescient in retaining their fate in their own hands.

St. John of Nepomuk

The first Czech Church built west of the Mississippi, this parish once anchored the bohemian immigrants who settled here in the mid to late 1800’s. The present parish closed in 2005, but the church—constructed in 1897—remains active as a chapel, albeit with aging and dwindling members. The holy edifice and surrounding building have been designated as an historic district, which helps but does not guarantee future viability.

Sts. Peter and Paul.

Founded in 1849 in historic Soulard, the original church members employed skilled stone artisans to construct this magnificent Gothic church completed in 1874. Massive stonewalls support beautiful stain-glass windows and a soaring ceiling, topped by a towering spire that oversees a much-changed City. Today, three-quarters of its membership resides outside traditional parish boundaries.

St. Peter and Paul provides both a food pantry as well as a haven—that includes showers, laundry and lockers—for up to seventy homeless people in a shelter located beneath the altar in the subfloor of the church.

The parish attempts to meet part of its financial costs by offering the church for weddings, and the neighboring Franklin Room for receptions. One hopes that the Diocese opts to keep this useful parish open rather than robbing Peter to pay Paul.

St. Ambrose (The Hill)

The envy of inner city parishes, the Italians secured the good fortune of taking root in the southwestern portion of the City farther removed from more difficult urban environs. Humble single-family homes—rather than flats and four-family apartments in so much of the inner city—persevered an intact and geographically protected neighborhood.

The beautiful St. Ambrose church was built in 1907. The grade school, along with The Hill neighborhood of restaurants and stores, continues to flourish, and will likely draw more students from neighboring parishes that may close in the future.

4 replies on “HISTORIC CHURCHES PARALLEL ST. LOUIS’ PAST AND PRESENT”

big congregation reading this story

I’ve had the pleasure to go to services in more than a few St. Louis city Catholic Churches. Thanks for your hard work on the research it took to tell the story.

Great piece, wish our civic leaders would realize what treasures these churches are and figure a way to salvage them. As this piece articulates these are truly works of art inside and out, superb craftsmanship that you don’t see today.

I knew I wanted to read the piece, but at a time when I could sit down and really digest it. I greatly enjoyed the detailed descriptions of the construction of the churches and their congregations, and their significance in St Louis history. You must have spent a great deal of time researching the parish histories.

The entire time I was reading, I kept thinking how much my father would have enjoyed the summary. He probably would not have been too interested in your different articles on sport figures and musicians, (other than the fact that you wrote them,) but I know he would have loved all of your stories on history, political issues, and travel. I wish he could have had the chance to read them.